“A game is a series of interesting decisions.”

— Sid Meier, game design pioneer

Head in the Clouds is a board game that I’m working on with my fiancee. It is inspired by and takes mechanics from the engine building, open drafting, and worker placement genres. Great sources of inspiration are Splendor and Everdell.

Pillars and design goals

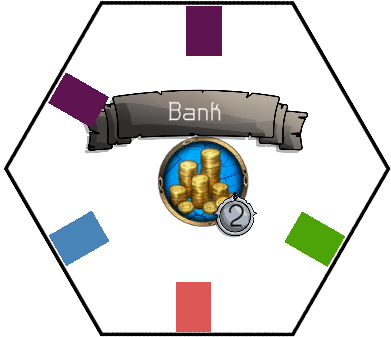

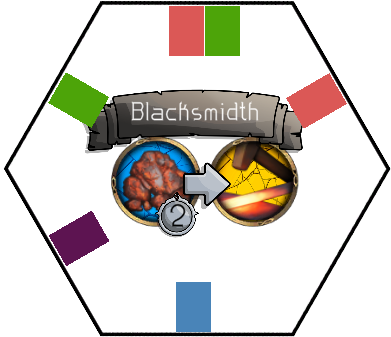

The first pillar of Head in the Clouds is actually a mechanic. In this worker placement game, a player is able to overtake a location from another player by committing a surplus of workers there. For lack of a better term, I will call this mechanic superseding. This means that most locations yield resources asynchronously, otherwise there would be no point in superseding other players’ workers. This is the mechanic that has stood the test of time throughout all of the iterations of the game and gives the game an element of push your luck. Is a player going to commit more workers to a location for a sure gain, or will she try to go for a more risky move, knowing the location she wants might be superseded later, before reaping the benefits of her labor?

Another pillar that we defined for Apotheracy’s Guild is simplicity. Whenever we dream up a new rule or mechanic, it should give the game more depth, not more complexity. This is also why Splendor was one of our major inspirations; it can be taught in minutes. The depth of the game arises not from the complexity in rules, but from the gamestate itself. Every decision a player makes is driven by and influences the gamestate.

Finally, we wanted to create an experience where players work on an engine, to give a sense of progression. Buying cards and using them is the core of that engine and players need resources to buy those cards. This is where the core gameplay loop closes.

Evolution

Iteration 1

In earlier versions, I worked with seasons. Players would take turns placing their workers on different locations on the map or superseding locations. Then the season would end and the players withdrew their workers and gained the resources depicted on those locations.

Another big part of these early iterations were guilds. There were four guilds in total, and cards of the same guild reinforced each other. This gave the game a layer of open drafting; will a player buy something that works really well for herself or does she buy something that she knows someone else needs (hate drafting)?

The above cards are both from the same guild. They can be activated once per round by the player who bought them, but the second card (Bishop), needs to spend (tap) two other cards of the same guild. Tapped cards can no longer be activated or spent until they are untapped, which happens at the end of each season.

This concept worked reasonably well, but people were mostly invested in the worker placement part on the map and the cards didn’t add much to the overall experience of the game. Furthermore, because cards could be activated once per season, it meant that the game became quite boring (every guild member was activated once per round, making the game sluggish and predictable).

Iteration 2

To tackle this problem of cohesion between the map and the cards, I came up with a concept in which a player had to play her cards on a separate player board to activate them.

In the below example, a player first plays the Legislation card, which she can immediately resolve to send any of het opponent’s workers (soldiers) to prison to make it easier to then supersede the remaining workers from that location. In a subsequent turn, she plays the Automation card, which resolves immediately as well. Since the left border aligns with the Legislation icon, the Legislation card resolves again.

This adds a grid coverage mechanic to the game.

This iteration of the game presented players with a lot of interesting decisions (depth vs. complexity). However, it felt as though there were two separate systems competing for the player’s attention and unfortunately it meant that a turn either lasted a very long time (as players wanted to fully utilize their options) or players simply didn’t pay attention to their own player board.

Instead of fixing the problem of cohesion, this iteration enhanced it.

I will definitely revisit this concept later, because there is a lot of unexplored territory here that deserves a core gameplay loop of itself.

Iteration 3, 4, […], n

I tried various new versions to tackle this division of attention problem, with minimal results. Below is one such example of a mechanic I played around with. Players placed workers on locations on the main board and if a player’s workers remained on those locations, she placed them on her player board. If any colors matched, it would trigger a cascading effect, like in iteration 2.

By this time, the game was a lot less fun to play. What made iterations 1 and 2 fun and exciting (though they lacked cohesion), were now replaced by untested and often tedious mechanisms.

This is when I asked my fiancee to help me with the design process. We play a lot of board games together and she already helped me flesh out some earlier concepts so it felt only natural to ask her. I had to give up complete ownership, but we complement each other to a great extend.

The first thing we did was to revisit and discover what parts of the earliest iterations worked well and what parts specifically caused the game to feel incohesive. We decided to remove a lot of clutter that had sneaked up in the game and really focus on the core parts: using the board to gain resources, then spending those resources to play cards, which in turn made it easier to gather resources, etc.

In the concept version shown above, a player collects resources from the game board, then buys a fruits card, which gives her 1 fruit. When she collects 2 fruits this way, she can spend those fruits on higher tier cards (figs), eventually being able to buy cards worth a lot of points.

After some testing, we decided this iteration worked well enough, so we started adding back some mechanics we removed earlier.

Iteration n + 1

In this iteration, we changed the theme from guilds to alchemists (the name for this iteration was actually Apothecary’s Guild). You collect different resources to brew potions, which you then sell to customers. Potions grant a one-time effect and customers give a persisting improvement.

In the above example, a player pays resources she finds on the map and plays cards to gain the indicated potions. She can then activate the potions she played earlier to gain a one-time benefit. The third image is a customer who will buy potions and gives a persistent improvement to the player who buys it, as well as a large amount of victory points. The customers give the players a clearer goal to work towards, rendering the cards more elementary, which are therefore more integrated in the overall experience.

Something we changed was that we removed seasons, which speeds up the game dramatically. Players are now responsible for returning their workers on the right time.

Another thing we added that works quite well, is increasing returns. When a player places her worker(s) somewhere, she adds a resource to that location of a specific type, as depicted in the location. When she starts her next turn, that resource grows by one. This further increases the push your luck element, since if her potential benefit is greater and greater, it becomes ever more tempting for opponents to supersede her location.

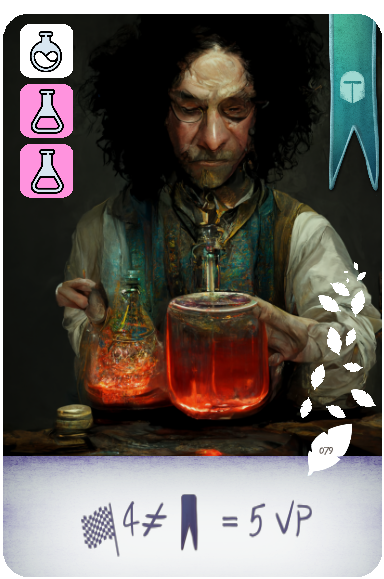

Iteration n + 2

In the previous iteration, there were a few things that players didn’t quite get. We were able to fix most of these issues with different quality of life (QOL) edits to the cards. There were also some systemic problems, one of which that players didn’t really feel a sense of progression, meaning that turn 1 and turn 10 felt very similar in nature. Without this sense of progression, players don’t get a lot of meaning from their choices, because they don’t seem to impact the rest of the game very much. To counter this (and some other problems), we have added a new feature, the banners. Each customer has one or more banners printed on the card (see image below). When a player plays them, she invests in a certain banner type; the more banners she has of a specific type, the more victory points she will get for that type, each banner adding an increasing number of additional points: the first banner of a type is worth 2 points, the next ones 3, 4, 5 and finally 6, making a complete set of 5 banners worth 22 points.

As is shown in the picture above, these cards give a persistent improvement as well, either granting a new power that can be used each turn (left customer card), or a way to score extra victory points at the end of the game (right customer card). The recipe card in the center gives the player potions to buy customers with.

Another thing we added, to give players more meaning to their actions, and being able to have clearer goals is something that a playtester brought to our attention: whenever a player finishes an x amount of a specific banners, they will gain bonus victory points indicated on the bonus card. This is also tied to the end game trigger: there are a total of five of these cards, whenever three have been collected, the game ends, making sure the game doesn’t drag on too long. These cards can be seen below.

Future

There are still some problems to iron out. First of all, the superseding mechanic feels quite take that like. Not everyone likes that kind of interaction, especially if not all players are competitive. Right now, the location’s excess returns are reset. This means that if you supersede another player, that player has no other option than to conclude it happened because you wanted to annoy me. This is a problem we haven’t been able to resolve yet.

We also want to add one more layer of cards and remove the one-time effects of potions. You can either sell your potions to customers gaining many victory points, or drink the potion yourself (which is another card) to get a persisting improvement.

Learnings

Not everyone’s feedback will improve your game

It’s good to listen to your playtesters’ feedback, but not every piece of feedback will enhance your game. Sometimes players just don’t like your game or the genre of game you are making. Your playtesters don’t know the vision you have for your game and might mention something that doesn’t fit your design at all.

Main take-away: Listen to your playtesters but don’t design your game for everyone.

Work with atomic iterations

As your game starts to take shape, start working with atomic iterations. By this I mean, don’t make changes that can’t be traced back. Test single mechanical changes and see how it interacts with the overall system. If you change the system itself too much, it becomes impossible to see where the fun got lost and how to retrieve it. It works much the same as with version control. Whenever something works well, make a commit. Store it somewhere, ready to revisit. This will save you lots of time in the long run.

Playtest systematically

We started keeping a playtest journal. I got the idea from a Kickstarter, called Fail Faster. This is a journal specifically designed for board game designers, in which it’s much easier to keep track of your progress. It also helps during the playtest itself, to take notes.

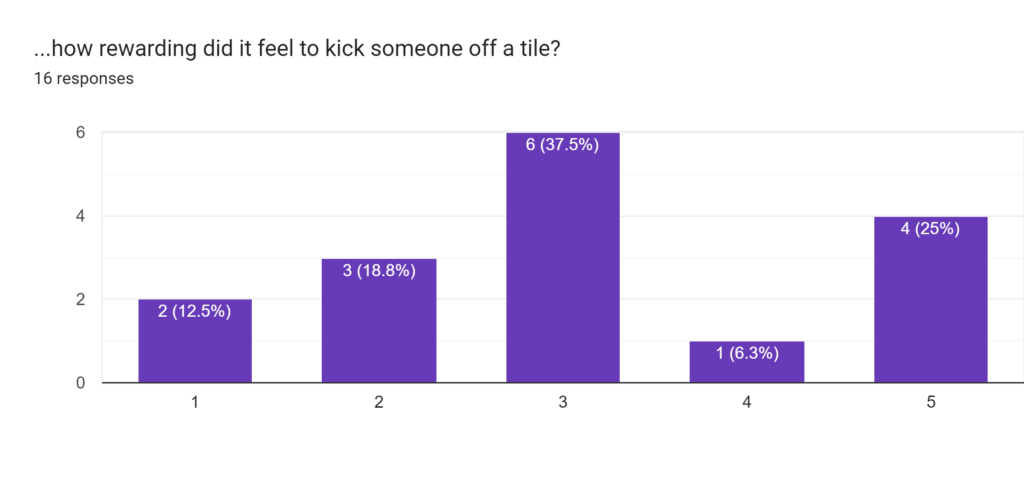

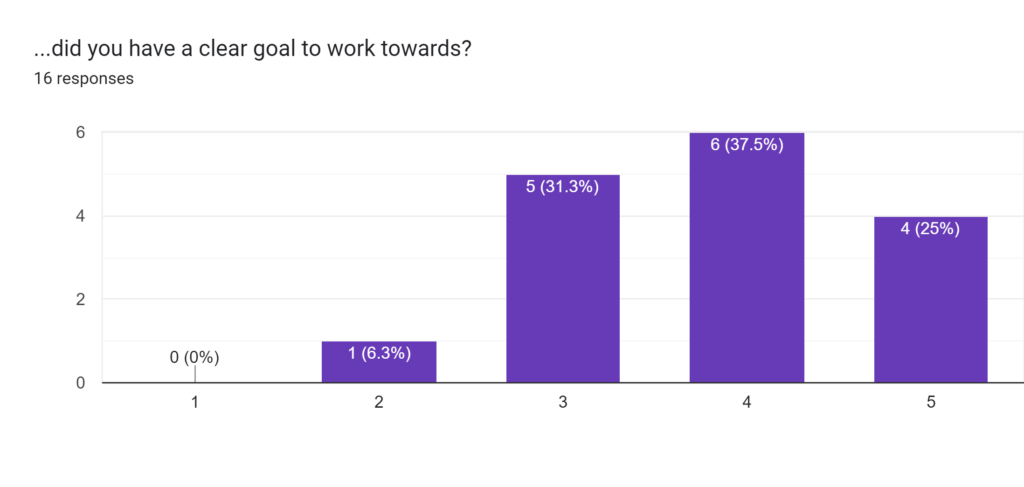

We started asking our playtesters to fill in a Google Form to get a better read on our playtester’s experience as well as being able to place versions next to each other and see whether the quality goes up or down as we iterate over new concepts.

Some sample questions are

- What is your favorie board game? If people filled in Monopoly or Catan here, we might take the feedback with a grain of salt.

- On a scale from 1 to 5…

Furthermore, we try to playtest with the same group more often. How does their experience change over time?

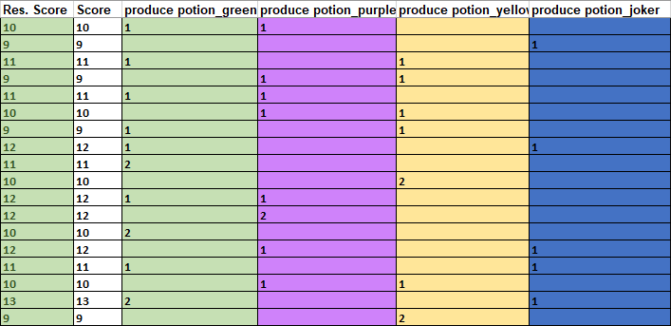

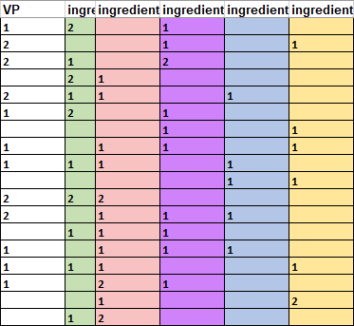

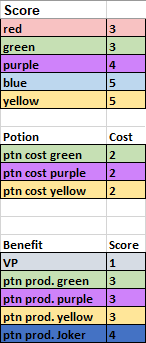

Work with Excel and automation

Microsoft Excel is a great tool to create spreadsheets. Assign a key value to each cost and gain (for example, some resources are more scarce than others) and see if they are equal. With simple Excel formulas like lookups, multiplications and additions, my live gets much easier.

Then, export a CSV and import that into your project. In my case, I use Unity to create templates of cards and set the values equal to the costs read from the CSV file and presto! I can print out and playtest a whole bunch of cards.

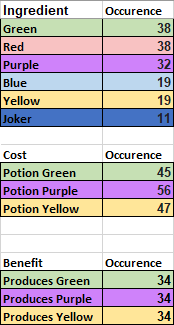

It’s much easier and faster to balance the game, as soon as resource score (cost) and card score (benefit) are not equal, there might be something off for a particular card. I can also see how many of each resource is in the game. In this case, yellow and purple potions are more abundant as a cost, but not more prevalant as a resource, that might be a problem. It might also mean that purple is more scarce, and therefore cards are more valuable creating a cost/benefit dynamic.

In any case, it’s good to see at a glance how much of each potion is in the game. Updating a particular key value (for example, making cards that cost purple potions reap more benefits, because they are scarcer), allows me to immediately see all the affected cards.

Leave a Reply